The rich are not like you and me…

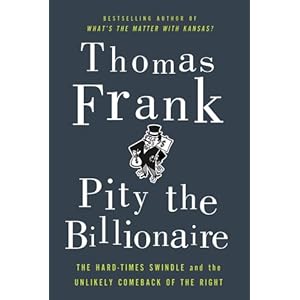

Pity The Billionaire by Thomas Frank

Thomas Frank spends this book doing what he does best – analyzing why, in spite of historic trends which say otherwise – much of the politically active population of the United States espouses and defends policies and ideas which are contrary to their own best (economic) interests.

This is a restatement of Thomas’s thesis from “What’s the Matter With Kansas” with a focus on the political situation post-Great Recession. Like his earlier book, Thomas is puzzled why so many average Americans are seemingly choosing ideology over what actually benefits them economically. In this case, sympathy for billionaire bankers and their political supporters (couched in the rhetoric of defending capitalism and free enterprise) over policies – such as economic and health care reforms – which might actually benefit middle class folks directly.

I approach politics from a liberal viewpoint, but Thomas seems to fall into the same bit of blindness that affected “Kansas” – namely, he is shocked to see a group of Americans hewing to ideology over their own material self-interest. At least it is shocking and dismaying when these folks are middle-class Americans from the flyover states. This shouldn’t be surprising. Ever since the late 1960s and the rise of the modern political environment, large swaths of Americans focus more on ideology over their own self-interest – liberals and conservatives (how many wealthy Manhattanites voted for Obama in 2008 even though his proposed policies might have hit them in the pocketbook?)

Nonetheless, Thomas has written a fairly incisive book, and one which is rather depressing, if only as a catalog of the myriad of ways that a more imaginative or energetic Democratic party or President could have responded to the crisis. In the end, the President ceded the ideological battleground to his opponents, and like French generals in World War II, seemed most interested in negotiating his own defeat rather then using imagination (and the significant resources still at hand) to try to actually win.

Thomas’s book is a depressing reminder of the state of American politics today, and a fair look at the Tea Party and other forces (including a great side-trip into the depths of Ayn Rand’s oeuvre) who have been driving the debate in the country the past two years. He tells it like it is, and depressed liberals (as well as triumphant conservatives who aren’t afraid to read a book by someone on the left) will be both enraged and enlightened.